Introduction:

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune condition that arises when our immune system incorrectly targets own body’s tissues. It is a significant public health concern that can cause significant disability and reduced quality of life.

The immune system targets the synovial membrane that lines the joints by error in RA, causing inflammation and joint degeneration. As a result, the joints experience discomfort, stiffness, and swelling, particularly in the hands, wrists, and feet. Joint injury can cause malformation and dysfunction over time.

Prevalence:

Rheumatoid arthritis is predicted to affect 0.5-1.0% of the global population. In Southern Europe, including Greece, the prevalence rate is as low as 0.18-0.34%. Conversely, the prevalence rate in native American Pima Indians is as high as 5.3% and 6.8% in Chippewa Indians.

The global incidence of RA varies, with a larger prevalence in developed nations, which may be explained by exposure to environmental risk factors, but also by genetic variables, different demographics, and under-reporting in other areas of the world.

Causes:

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic autoimmune condition caused by autoantibodies such as rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody. Synovitis, bilateral joint swelling, and pain in the tiny joints occur in the early stage. The joints become deformed as the disorder continues, the inflamed areas extend to the wrists, knees, elbows, shoulders, and so on, and this joint deterioration has a significant influence on the patient’s everyday life.

Pathogenies:

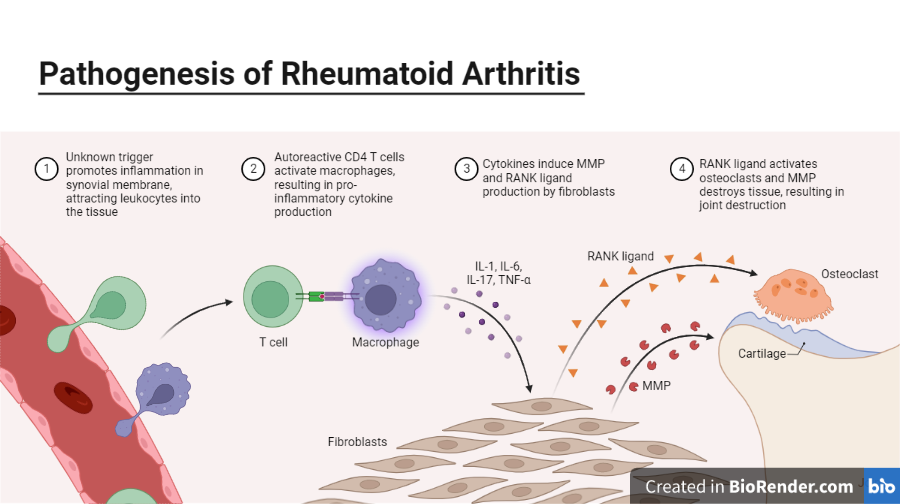

The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) involves a complex series of steps that ultimately lead to chronic inflammation and joint destruction. the pathogenesis of RA involves a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and immune system dysfunction, resulting in chronic inflammation and joint destruction. Effective treatment of RA aims to control inflammation, prevent joint damage, and improve quality of life. Here are the main steps involved:

Genetic predisposition: Certain genetic factors are known to increase the risk of developing RA. For example, specific variations of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes, especially the HLA-DRB1 gene, are strongly associated with the development of RA.

Environmental triggers: Various environmental factors such as smoking, infections, and hormonal changes are believed to trigger RA in genetically susceptible individuals.

Activation of the immune system: Once triggered, the immune system becomes activated and recognizes joint tissue as foreign, leading to an immune response against the joint synovium. The synovium is the tissue that lines the joint capsule and produces synovial fluid, which lubricates and nourishes the joint.

Inflammatory response: The activated immune cells, including T cells, B cells, and macrophages, release cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), that promote inflammation and attract more immune cells to the joint. Induced peptidyl arginine deiminases (PADs) can alter peptides by converting arginine to citrulline. After being processed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells, modified proteins are then given to T cells (DCs). While these processes can occur in the mucosa, they can also occur in central lymphoid organs, resulting in local and systemic antibody production directed against the changed peptides. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) and cytokines gradually build in the bloodstream in the years preceding the onset of RA symptoms.

Fig: Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Formation of the pannus: The inflammatory process triggers the proliferation of synovial cells, leading to the formation of an abnormal tissue called the pannus. The pannus invades the joint cartilage, causing erosion and destruction.

Bone erosion and joint destruction: The inflammatory cytokines also activate osteoclasts, which are cells that break down bone tissue, leading to bone erosion and joint destruction.

Chronic inflammation: The ongoing inflammation causes persistent joint swelling, stiffness, and pain, leading to functional impairment and disability.

Types:

There are various varieties of rheumatoid arthritis, and knowing which type will help to decide on a treatment plan. The kind of RA is determined by the symptoms as well as the clinical results of laboratory testing and x-rays. The presence or absence of an autoantibody or protein produced by the body when it begins fighting the immune system, known as the rheumatoid factor, can distinguish distinct types of RA (RF). Although RA can exist without a positive RF test, its presence helps to identify the type of disease existing in the body. According to studies, more than 80% of persons with rheumatoid arthritis test positive for rheumatoid factor, a condition known as positive (or seropositive) rheumatoid arthritis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may have a constant negative rheumatoid factor test, and this milder form of rheumatoid arthritis is termed as negative (or seronegative) rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid Factor Positive (Seropositive) RA

Rheumatoid Factor (RF) is an antibody that the immune system produces in response to infections or autoimmune illnesses. Rheumatoid Factor Positive (RF+) refers to the presence of RF in the blood, which is common in rheumatoid arthritis patients (RA). The existence of these antibodies suggests that the patient’s immune system has launched an attack on their own tissues, resulting in persistent inflammation and tissue damage in joints and possibly other organs. Seropositive RA is frequently associated with significant joint destruction and an increased risk of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease.

Rheumatoid Factor Negative (Seronegative) RA

It is a subtype of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in which a patient has typical RA symptoms but no rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies are found in their blood. Seronegative RA accounts for around 20-30% of all RA cases and is typically less severe than seropositive RA. If left untreated, it can cause considerable joint damage and disability. Seronegative RA may be more prevalent in men and younger people. The absence of RF and anti-CCP antibodies makes it difficult to distinguish seronegative RA from other inflammatory joint diseases. Seronegative RA can be diagnosed by clinical examination, imaging tests such as X-rays and MRI, and joint fluid analyses.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an arthritic condition that affects children under the age of 16. It’s sometimes referred to as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) or juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA) (JCA). JIA is a chronic disorder characterized by joint inflammation, discomfort, and stiffness that, if left untreated, can lead to joint damage and disability.

JIA development may also be influenced by genetic factors. Joint discomfort, edema, stiffness, reduced range of motion, exhaustion, and a low-grade fever are all symptoms of JIA. A clinical examination, blood tests, imaging examinations, and joint fluid analyses are used to diagnose JIA.

Felty syndrome

Felty’s syndrome is a rare and severe variant of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that affects only a small proportion of RA patients. It is distinguished by the presence of RA, splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), and neutropenia (low white blood cell count). The precise etiology of Felty’s syndrome is unknown, although it is thought to be an autoimmune condition in which the immune system incorrectly assaults the body’s own tissues, such as the joints, spleen, and bone marrow.

Palindromic rheumatism

Palindromic rheumatism (PR) is an uncommon kind of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurring episodes of joint pain, swelling, and stiffness that last hours to days. The name “palindromic” refers to the fact that the symptoms appear to reverse themselves and the joint recovers to normal between bouts. The precise etiology of PR is unknown, although it is thought to be an autoimmune illness in which the immune system targets the body’s own tissues, including the joints. PR development may also be influenced by genetic factors.

Still’s disease

Still’s disease, commonly known as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA), is an uncommon kind of inflammatory arthritis that primarily affects children but can affect adults as well. It is distinguished by fever, rash, joint pain and swelling, and systemic inflammation that can impact many organs and tissues. Still’s disease has no known etiology, although it is thought to be an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system mistakenly assaults the body’s own tissues, such as joints, skin, and internal organs. Genetic factors may potentially play a part in the condition’s development.

Fever, rash, joint discomfort and swelling, exhaustion, muscle weakness, and inflammation of organs such as the heart, lungs, liver, and spleen are all symptoms of Still’s disease.

Signs, Symptoms and complications:

RA has a disease progression that can begin several years before clinical symptoms appear.

- Joint pain

- Joint swelling

- Joint stiffness

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Numbness and tingling

- Warmth and redness

If left untreated or poorly managed, RA can lead to several complications that includes joint damage, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, lung disease, Anaemia, Eye problems, Lymphoma, Dry eyes and mouth, and abnormal body composition.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of RA is usually made by a healthcare provider based on a combination of factors, rather than a single test or symptom.

| Method | Description |

| Medical history and physical exam | Detailed medical history and physical examination to assess symptoms such as joint pain, stiffness, swelling, and limited mobility |

| Blood tests | Tests for inflammation and autoimmunity, including rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies, C-reactive protein (CRP), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) |

| Imaging tests | X-rays, ultrasounds, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to visualize joint damage, swelling, and inflammation |

| Synovial fluid analysis | Removal of a small amount of synovial fluid from an affected joint and analysis for signs of inflammation and crystal formation |

| ACR/EULAR classification criteria | Criteria used to help diagnose RA and may include a combination of clinical symptoms, laboratory tests, and imaging results |

Molecular Diagnosis:

HLA (human leukocyte antigen) testing is a form of genetic test used to aid in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Testing for the HLA-DRB1 allele, which is part of the HLA gene complex, can assist identify those who are predisposed to having RA. HLA testing is often utilized as an adjuvant to other clinical and laboratory tests rather than as a solo diagnostic tool for RA. HLA testing, in addition to assisting in the identification of persons at elevated risk of RA, can also be used to discriminate between distinct subtypes of the disease, such as seropositive and seronegative RA.

Additional genetic markers linked to an increased risk of RA include changes in the PTPN22, STAT4, TRAF1/C5, and TNFAIP3 genes. These genes are implicated in several areas of the immune system, including cytokine signalling, B-cell and T-cell activation, and inflammatory regulation.

While genetic markers can help identify individuals who are at a higher risk of developing RA, they are not reliable diagnostic tools on their own. RA is normally diagnosed using a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and laboratory investigations, including screening for inflammatory markers and autoantibodies.

Prevention and Treatments:

Strong trends in the severity of RA have likely reflected changes in therapy paradigms and overall better disease management during the last three decades. It’s crucial to remember that each person with RA may require a unique combination of drugs based on their symptoms and disease progression. As the condition advances, treatment options may also vary.

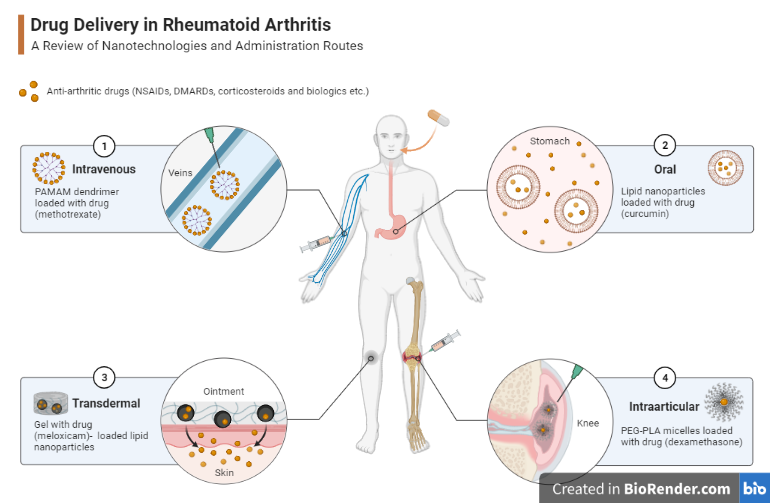

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): These drugs help to reduce pain and inflammation, but do not affect the progression of RA. Examples include ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs): These drugs are used to slow the progression of RA by suppressing the immune system. Examples include methotrexate, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and hydroxychloroquine.

Biologic DMARDs: These drugs are a newer class of DMARDs that target specific proteins involved in the immune system’s inflammatory response. Examples include adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab.

Corticosteroids: These drugs are used to reduce inflammation and can be given orally or injected directly into the affected joint. They are usually used in combination with other medications.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors: These drugs block specific enzymes that contribute to inflammation. Examples include tofacitinib and baricitinib.

Fig: Drug delivery in Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

There is no known way to totally avoid rheumatoid arthritis (RA), as the specific etiology of the disease is unclear. However, there are several activities that can be taken to lessen the chance of getting RA or to postpone its beginning. While these methods may help to lower the risk of acquiring RA, it’s crucial to realize that anyone might have the condition, even if they follow these guidelines. Speak with your healthcare practitioner if you are concerned about your chance of having RA.

Maintaining a healthy weight, quit smoking, eating a healthy diet (high in vegetables, fruit, olive oil, nuts and wholegrains), getting regular exercise, manage stress, joining a self-management education class, only moderate alcohol consumption, maintaining vitamin D in a healthy range may help to reduce the risk.

References:

- Arima, H., Koirala, S., Nema, K. et al. High prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and its risk factors among Tibetan highlanders living in Tsarang, Mustang district of Nepal. J Physiol Anthropol 41, 12 (2022).

- Finckh, A., Gilbert, B., Hodkinson, B. et al. Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 18, 591–602 (2022).

- Zamanpoor, M., 2019. The genetic pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic insight of rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical genetics, 95(5), pp.547-557.

- Nakken B, Papp G, Bosnes V, Zeher M, Nagy G, Szodoray P. Biomarkers for rheumatoid arthritis: From molecular processes to diagnostic applications-current concepts and future perspectives. Immunol Lett. 2017 Sep; 189:13-18

- Yarwood A, Huizinga TW, Worthington J. The genetics of rheumatoid arthritis: risk and protection in different stages of the evolution of RA. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016 Feb;55(2):199-209.