Introduction to Fasciola hepatica:

Fasciola hepatica is a hermaphroditic trematode with a complex life-cycle that includes an intermediate (snail) and definitive (mammalian) host. The earliest known trematode or fluke was F. hepatica. However, it was initially found in sheep rather in humans. The disease, known as liver rot, is brought on by consuming metacercaria from contaminated freshwater foods like watercress and water chestnuts.

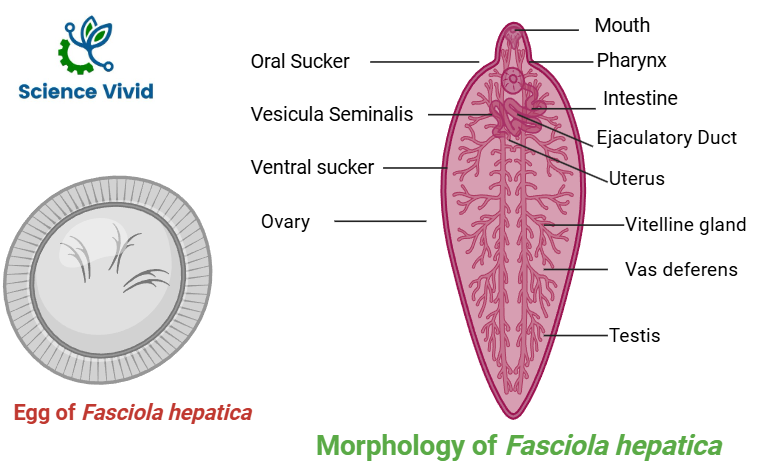

The adult worm is a parasite that resembles a leaf and is dorsoventrally flattened. It lives in the biliary channels and secretes an average of 9000–25000 eggs every day. It has a ventral oral sucker, uterus, testes, intestinal system, and surface spines.

Fig: Morphology and egg of Fasciola hepatica

Clinical manifestations:

F. hepatica infections can present with a wide variety of clinical symptoms, from prominent gastrointestinal problems to an asymptomatic state. The flukes cause inflammation, bleeding, dilated intrahepatic bile ducts, subcapsular cavities, and surface liver nodules when they enter the liver and break down hepatic tissue. There are two stages to the sickness, and only a small percentage of patients exhibit extraintestinal symptoms.

Acute Hepatic Phase

Abdominal discomfort, fever, and hepatomegaly are the classic trio of symptoms and indicators that follow the excysted metacercaria’s penetration of the duodenal wall, entry into the peritoneal cavity, and migration through the liver over a period of two to four months.

Chronic Obstructive Biliary Phase

The disease’s chronic phase starts once the worm enters the biliary tree. An asymptomatic latent phase may exist, lasting anywhere from a few months to several years. The inflammatory alterations in the bile ducts and the mechanical impacts of the worm, which may result in biliary obstruction, are prominent characteristics of the chronic phase. It is unknown what proportion of patients may develop cholecystitis and cholangitis.

Diagnostic Methods:

Fasciola hepatica after first penetrating the host duodenal epithelium, freshly excysted juveline moves into the peritoneal cavity, host liver parenchyma, and bile ducts. The diagnosis depends on the identification of antibodies because the parasites do not generate eggs during tissue migration. After the first infection, antibodies against Fasciola may take two to four weeks to show up, and they should stay positive throughout the chronic phase. Parasites begin to produce eggs that can be found in stool after they reach the biliary tree.

Stool microscopy

Fascioliasis cannot be diagnosed with a gold standard test. In endemic nations, fascioliasis is mostly diagnosed by stool microscopy testing. The presence of eggs in the feces confirms the diagnosis. Low egg counts, which can be seen in chronic infections, treatment failure, or infections with hybrid parasites (F. hepatica/F. gigantica), further diminish sensitivity. The WHO recommends the Kato Katz test, a quantitative microscopy test, in regions where infection prevalence and intensity are high. The operculated ova are 140 x 75 µm and have a yellowish-brown color. A higher sensitivity can be achieved by combining the Kato Katz test with techniques that concentrate eggs, as the test alone may miss around one-third of the infections. Kato Katz is less sensitive than sedimentation tests like spontaneous sedimentation and Lumbreras quick sedimentation. The highest sensitivity is achieved by device-based concentration approaches, but they are costly, challenging to employ in large surveys, and not universally accessible. Compared to direct smear, Kato Katz, formalin-ether, and basic flotation methods, the FLOTAC and mini-FLOTAC devices in conjunction with flotation solutions with particular gravities modified for Fasciola eggs are thought to be more sensitive.

Antigen detection method

The best methods for diagnosing hepatic fasciolasis are coproantigen detection assays. Its sensitivity and specificity are adequate. Coproantigen detection can assess a large sample size for a community survey. It may identify the antigen during the acute, early (about two months prior to egg shedding), and chronic stages of infection. It can be used for re-infection detection and post-treatment monitoring. It works well for identifying infections in people who shed very few eggs. Sandwich ELISA utilizing polyclonal, monoclonal, or both antibodies is the main method for detecting antigen in stool samples. Patients with fascioliasis may also have fasciola antigen in their urine.

Nearly two weeks after infection, or two to three months before eggs appear in the feces, antibodies can be found. Both acute fascioliasis and chronic fascioliasis can be diagnosed with serological testing when the parasite eggs are still not being generated. Several antigens have been tested in a range of immunodiagnostic techniques for the diagnosis of Hepatic Fasciolasis, including crude extract of Fasciola hepatica or Fasciola gigantica, ES antigens, refined antigen from ES or crude antigen, synthetic, and recombinant antigens. Patients with ectopic fascioliasis or encapsulated worms in liver abscesses may experience false negative results. Antibody detection assays and coproantigen testing cannot distinguish between Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica.

Molecular and Nucleic Acid-Based Detection

The sensitivity and specificity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Fasciola DNA detection in stool samples are generally very good. Weeks before eggs are visible in the stool, some PCR tests can identify Fasciola DNA. Fascioliasis in humans (Target: internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) area) is diagnosed by conventional PCR and a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) test with stool microscopy and serology, both of which have very high analytical sensitivity. Targeting the ITS1 region of the rRNA gene, recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) offers great potential for field application in underdeveloped nations.