Introduction to Dengue Virus:

Dengue is a mosquito-borne disease caused by the skin inoculation any of four antigenically different serotypes of the Dengue virus (DENV 1-4), characterized by wide spectrum of illness ranging from asymptomatic to severe forms. As the name ‘breakbone fever’, the patient complains of pain in the back, joint, muscles and the eye balls. Incubation period ranges from 3-14 days of the infection with the sudden onset of fever with occasional association of malaise, chills and headache. There is no protection against secondary infection with a heterotypic serotype

Epidemiology and Transmission:

Aedes aegypti, A. albopictus and A. polyniensis are the principal vectors for the transmission of Dengue. While A. aegypti serve as the vectors of urban cycle of Dengue and growing in the indoor environment, A. albopictus are the vectors of rural environment and can breed even in the natural water reservoirs. Man are the only reservoirs for the urban cycle while in the sylvatic cycle monkeys may also act as reservoir.

Viral Morphology:

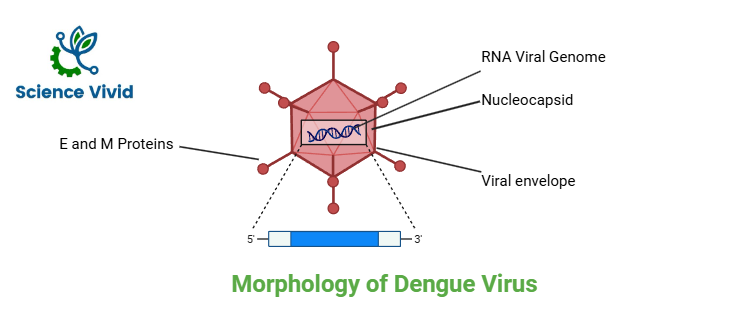

Dengue virus is the member of the genus Flavivirus belonging to family Flaviviridae. It is an enveloped, spherical shaped virus with the diameter of around 50nm. The genome contains the single stranded RNA of positive polarity about 11kbp in length. The genome is bounded by the carboxy- and amino- terminals of the Capsid/ Core (C) protein that collectively forms the nucleocapsid core of the virus about 30nm in size. The virus envelope is host derived and is composed of the lipid bilayer that accounts for about 17% of the total viral weight. The lipid envelope is anchored by the outer and the most antigenic Envelope (E) protein and the membrane (M) protein via the transmembrane anchor.

Envelope (E) protein

The glycosylated envelope protein interacts with the viral receptors on the host cell membrane and mediates viral- cell membrane fusion.

Membrane (M) protein

Non-glycosylated membrane protein is a small proteolytic fragment of the precursor (Pre-M) protein. It is important for the maturation of the virus into an infectious form.

Capsid (C) protein

Capsid protein is highly basic in nature. The highly basic residues at the N- and C- terminals help to bind the genomic RNA while the central hydrophobic portion interacts with the cell membranes probably to aid in the assembly of a virion.

Fig: Morphology of Dengue virus

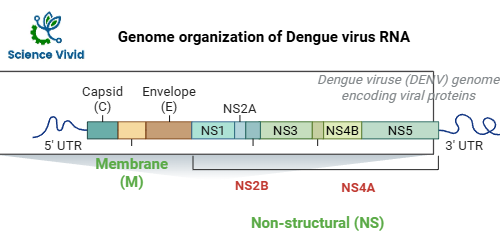

Genome organization of Dengue Virus:

The genome of the virus is a single-stranded RNA molecule with positive polarity that can function as mRNA directly. The 5′-cap is present in the genome, but the 3′-poly A tail is absent. The genome is converted into a single long polypeptide that is broken down into three structural and seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) by the host cells and viral proteases. The RNA replicase enzyme is known to be found in NS1, NS3, and NS5 of the seven NS proteins.

Fig: Genome organization of dengue virus RNA

Dengue Virus Replication Cycle:

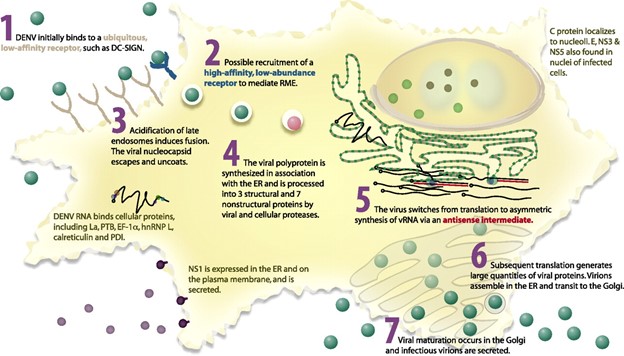

Through the interaction of the E protein, the virus binds to the clathrin-coated pits on the surface of the host cell, facilitating its uptake through receptor-mediated endocytosis, which confines the virions in the pre-lysosomal vesicles. The nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm and destroyed there thanks to acid-catalyzed membrane fusion and a conformational shift in the E protein. In addition, the virus can enter the host cell through the process of antibody dependent enhancement (ADE), in which the Fc region of circulating antibodies interacts with particular cell receptors (FcγR) to accelerate absorption when the surface E protein attaches to the antibody. The structural and non-structural proteins needed for the virus’s replication and assembly are translated by the genomic RNA, which now functions as the mRNA. The complementary minus strand, which now serves as the template, is initially transcribed by the replicase enzyme after translation for the production of viral RNA. Before being released, the virions mature by passing through the Golgi apparatus after assembling in the endoplasmic reticulum vesicles.

Reference: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01257-06

Fig: Intracellular life cycle of dengue virus

Pathogenesis and Immune Response:

The exact mechanisms that underlie the clinical manifestations of dengue infection are still unclear and complicated. The dengue virus first targets Langerhans cells and keratinocytes after being deposited in the dermal layer. These cells then spread the virus to tissue macrophages in various organs via the circulation, resulting in a primary viremia. The virus continues to circulate within infected macrophages during this phase, which usually lasts for five days. At the same time, it robustly replicates in epidermal tissues and the lymphoid compartments of the spleen. The amount of circulating viral load is influenced by the dengue virus’s strong tropism for dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages as well as its capacity to infect endothelial cells, hepatic cells, and bone marrow stromal cells.

Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever and Shock Syndrome:

Infection of macrophages, hepatocytes, and endothelial cells triggers programmed cell death (apoptosis), although some cells succumb through necrotic pathways that release inflammatory and toxic mediators. These cellular events, in turn, activate both coagulation and fibrinolytic cascades. Depending on the severity of bone marrow involvement and cytokine dysregulation, hematopoiesis becomes impaired, resulting in reduced platelet production. Combined with platelet dysfunction, this contributes to the vascular instability characteristic of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Concurrently, antiviral immune responses may generate antibodies and cellular reactions that inadvertently cross-react with host tissues, enhancing vascular permeability and promoting coagulopathic tendencies. The situation may be further intensified by the presence of heterologous IgG antibodies generated from a previous infection with a different dengue serotype. Collectively, these mechanisms culminate in the severe coagulation abnormalities and plasma leakage observed in Dengue Shock Syndrome.